I am a door dasher now.

At five p.m., I sit in the car looking at the dark phone. After a moment, the phone dings and illuminates. I push the button that has appeared on the screen. The fake woman’s voice of the navigation program directs me through traffic to a restaurant; I go inside, tapping sequential buttons on the phone. I identify, by receipt, the correct bag of food from a shelf with many plastic bags of food. I take a picture of the bag of food, and the receipt, with my phone, and the phone dings and illuminates again, like I’ve attained a level on a video game. The navigational woman - whom I hear as now snide, now aloof, now idiotic depending on the clutch and jerk of traffic - directs me to somebody or other’s house. Occasionally, I hand the bag of food to a person. More often, the portal on the phone instructs me to leave it at a closed door. Sometimes I have to type in a pin, provided by the phone, to get through vestibules to the interiors of apartment hallways, empty and long. I put the bagged food on a doormat and take another picture with my phone. Upon completion of this mission, the phone hums at me with electronic delight. It tells me I just made four dollars. I haven’t reached the car yet when the phone dings, glows, and invites me to my next mission.

Now my car smells like fried chicken. This doesn’t go away. Not even with the windows down. I promise myself an air freshener: maybe after four more dollars.

“How has it come to this?” I ask the lady in the phone, or god, or myself. It’s unclear. I look around, aching to see a human being. And they are there; there are people behind closed doors in a long silent hallway of closed doors, or encapsulated in a vehicle on the freeway just like I am, talking to electronic people just like me. I have the sense that this experience ought to be interactive, public, a little slice of humanity and it almost is; it almost feels social, but never quite. I walk into and out of McDonalds, Chik-fil-A, Panda Express, Applebees, Taco Bell and KFC. People order a single ice cream drink, or one chicken sandwich. I picked up one order of five double sized paper bags and a single cup of coffee at Kwik Trip: the receipt begins with the coffee, one donut, another chicken sandwich, and continues to forty-five other single serve and individually wrapped items. The receipt is two feet long, drifting against my thigh. I am confused about economics, about the alphabet in modern America, and about human conversation. I am also confused about the number of chicken sandwiches Americans eat, apparently all alone.

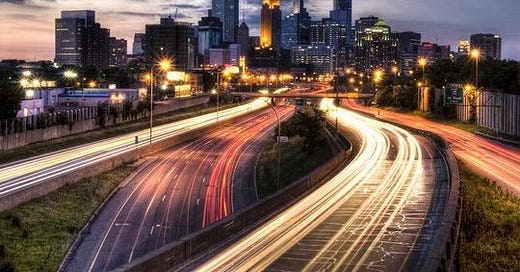

When the phone finally directs me to an independent restaurant for a burger, I irrationally feel comradeship for a fellow foodie. When I occasionally take the bag of food from a waiter’s hand, I try to meet their eyes. I feel my hand spitz with a desire to brush their own. There is a static feeling in my limbs, and a haze in the air. Some of the haze is wildfire smoke. Minneapolis air quality is ranking ‘dangerous’, the phone tells me. The traffic signs over the cloverleafs warn not about traffic but breathing. The phone lights up with two more dollars and then it goes dark.

It isn’t all bad. For a happy space of 45 minutes, just at the peak of summer evening, I buzz around a neighborhood where children play in the street and people walk on the sidewalks, apparently just enjoying a walk. Rosebushes sway and bumblebees lumber about. I hold a door open for another door dasher and comment on her pretty fingernail polish. She, being just five feet tall, beams up at me when she smiles. She and I squint at the receipts together, finding our mark. “Here you are,” she says, taking my elbow and turning me to the lower shelf, pointing with her chin. I soar out into the wealthy suburbs and ascend an emerald hill on a silvery driveway to a house like a glass cube; I ring the bell as directed and wave at the door camera. From this height there is a view of a park with people playing soccer in it. On the tennis court, someone is rollerskating in the slow, joyous, sexy private dance of their headphones. I turn on the jazz radio station in the car, lean my head back and close my eyes, ignoring the phone’s ding for a moment and listening to a trumpet and a snare drum. The smell of fresh cut grass kisses my face and then is gone.

“This is temporary,” I tell myself, or maybe the woman in the phone, or maybe god, but I am unsure what I mean. I don’t know how long this will last. I don’t know what it will lead to. My yoga students are dropping like flies, my monthly income nose diving for six months straight. I don’t know that it will bounce back, nor do I know if I want it to. “Write!” says some one or other, and I try to explain that all writers have other jobs: they are professors, or work in marketing. I have no degree, no work history aside from teaching yoga for almost twenty years. I cast about in my mind for some idea of what I would ‘like’ to do. There is no answer. I apply to a Barnes and Noble and am rejected within twenty four hours. G promises me this is AI, that no one actually read my resume: I am not personally rejected. I roll my face to the back of the couch.

I know that the door dashing - that gig work, generally - isn’t sustainable. Fifty percent of those four dollars will go to taxes. If I were to log gas and milage, the remainder would hardly be anything at all. But it’s for now. It’s to meet this month’s bills, buy this week’s groceries, pay down a vet bill.

Should I capitalize “Door Dashing?” I wonder, pulling up to a stoplight downtown. An unhoused man, slumped, carrying four backpacks, wild bearded and with a tremor in his hand, shuffles into the crosswalk. My turn signal clicks in the chicken smelling air. I look at the man in the crosswalk, eight feet in front of my car, and I realize I know him. I know his name. We used to be friends. We were teenagers, and then I moved away but when I came back I ran into him now and again. He had become a nurse. He worked at the big Salvation Army downtown. Standing one night on a lawn sipping iced tea, he told me of the unending sadness of the work and smiled, bravely. That must have been eight, nine years ago. Maybe more. He told me of treating exposure wounds on faces and feet, navigating the gap between a database and human beings, we whispered about mental health and loneliness and biography. I remember him as a gentle, sweet boy. His eyes were dark and limpid. He’d look at you steadily but without hardness, just a kind of unrelenting kindness, looking and looking at your face until you finally stopped looking elsewhere and met his gaze. Then he’d smile. I’d felt, the night of the iced tea, that he had the capacity for deep sorrow, the familiar to me marks of a soul open to a life of depression, the gentleness pending in a fifty fifty kind of way. He had a humaneness that simply made due; of course he decided to get a nursing degree and then work with homelessness.

The turn signal went on clicking. He shuffled slowly across the street. I wondered if I should call out, park the car, say, “Joel, is that you?” Had his compassion taken him too far? Had he fallen? What could I do? What was I supposed to do?

I was certain it was him, but can’t say I know absolutely. I mean I didn’t ask. I didn’t stop. The light changed. The lady in the phone directed me to change lanes in seven hundred feet. I ignored her and I watched Joel, everything I know about homelessness and choice and mental health evaporating too quickly for words up into the urban sky, tinged with the smell of fried chicken. I tasted my own adrenaline, which is metallic. I felt the grit of wildfires rimming my eyes. I waited until Joel or the man I thought was Joel stepped onto the opposite sidewalk, then I looked down in my lap, up into the rearview, and off ahead to the street I was turning into. I just drove away.

Sometimes in the summer, at just the right time in the evening, Minneapolis isn’t gray and brown and chrome. It becomes green and pink. Blues that have gold in it, gold that has red. The sky marbles, the river pearls, and all the buildings blush. It only lasts a little while, and then the sun goes down, and everything changes all over again.

Back home, I throw the phone onto the couch. It’s ten p.m. I stand in the middle of the room with my arms hanging. G folds me into his chest and whispers into my hair that it’ll be okay, he knows it will. It feels cruel not to answer, but I don’t have an answer; it’s all unclear so I don’t say anything. I just stand there. He holds me for a long moment, as if we are dancing. I remembered Joel dancing once, at a show. He kept his feet in one place. He just bent his knees and twisted his arms and chest, bouncing his head, smiling and keeping his eyes closed the whole time. It was like he knew he looked stupid, but was enjoying himself anyway. I remember calling his name, in that way you call out and lean to someone’s ear at a live show, your faces blue and white and dark and voices drowned out by the music. He opened his eyes and looked at me, laughed when I mimicked his dancing, and we went on dancing like that together: elbows cocked, faces up and down like Charlie Brown kids.

We all look so fucking stupid, I tell G. There is a gentleness that pends and a burn in the air. Everything feels fifty fifty. Like it can go either way.