Epic as soul work in devastating times

"But human life does not come back again / after it passes through the fence of teeth. No trade or rustling can recover it." Illiad 9.524-29, translated by Emily Wilson

Unhappy the country that breeds no heroes. No - unhappy the country that needs heroes. Bertolt Brecht, Life of Galileo

When I was sixteen and precipitously mediocre (see last post), I had a shaved head. I wore jungle boots over fishnet stockings. I found myself on an immersive cultural exchange program in rural Crete. I’d dropped or been kicked out of three schools already, and rather think they thought they could fix me up with hard work and the classics. The first week of our program was a sort of cloistered, boot camp orientation. We spent hours around tables organized in a rectangle learning The Rules. There was a rotating roster for chores and cooking. We were taken to the market and shown how to bargain while conducting ourselves respectfully. There were areas of town we should never go or never go alone. We should not swear on the street or wear loud American tee-shirts. We were allowed to sit in the cafes playing backgammon; it was fully expected we’d smoke like chimneys and drink the bitter wine, but we must never put our feet on the chairs or ever fail to acknowledge an elder. We learned to expect kisses and fondling, pinches of arm fat or pats on cheeks. I was given an extra rule, because of the shaved head: I was to always cover myself with a scarf if I wanted to step outside the house.

Greece, along with the Balkans and much of rural Italy, is considered a shame/honor culture according to cultural anthropologists. This is the stuff of vendetta, the evil eye, and chaperones. It is also the stuff of honor and respect, collectivism, and incredible demonstrations of social grace and hospitality. There is more care for upholding community than saving your own face in a shame/honor society. Japan, China, most of the Arab world, and many identity based communities like the Romani are further examples of shame and honor based culture.

There are three distinct models of social cohesion in this schema, although no culture fits perfectly into any of the models. The foundation for social life spans a spectrum from shame/honor, to guilt/innocence, to fear/dominance.

The quote unquote West is largely a guilt culture. It is individualistic and bound by legality rather than social bonds. Individual conscience is cultivated. Stuff like Catholic guilt and the American dream are consequent. Humanistic ideals fit here, with our civil rights and individual liberties. So too does libertarianism.

A fear/dominance based culture is organized by, well, terror. It’s mechanism is political and social repression. Leadership threatens harm, often targeted to specific groups. While the harm may or may not be enacted, actions by leadership inculcate a pervasive feeling of insecurity across society.

All cultural models are psychological, but fear cultures intentionally manipulate psychology through censorship, a sense of isolation, and a generalized belief that all channels of opposition and resistance are futile.

I’m not moralizing. Any cultural framework has both beauty and potential harm in it. The relationship of the individual to the collective is an ongoing question: current events slide toward a pervasive, toxic fear and away from laws meaning anything at all. It’s also important to point out that the quote unquote west has never been a purely guilt culture: the full privilege of law and individual innocence have only ever been available to some; threat wielding power has always defined ‘America’ to the enslaved, the colonized, the queer, and the femme.

The dawn and quick fire of the internet complicates all of these questions. We’re a mess of shame, guilt, and fear.

I am wondering about heroism. Honor, respect, and what is one to do.

I’ve been spouting off on the Gita precisely because it starts from fear and doubt. It starts with fear and then encourages us to live bravely. That’s a truncated version and there is a lot more to it, but the pervasiveness of ‘my god I am so scared’ and the Gita’s promise - hope, bare - seems important. It seems helpful.

And it is, helpful.1 It’s also hard. Our individualist worldview balks at any consideration of shame and heroism. To the extent that we live in fear, heroic behavior is unlikely. I can - do, often - talk about the Gita as literature, but I mostly live with it as a spiritual practice, which bends the meaning slightly. As a spiritual practice, the Gita becomes something more than literature while remaining all the important things literature is: it’s a way to survive life’s hardness. I believe, with Mariame Kaba, that hope is a discipline. It requires spiritual work. Spiritual work isn’t the same thing as self-improvement or self-help, or any of the frantic responses to suffering. It is very quiet, and very inward. It both cools and burns.

The Gita is born out of a warrior culture. That is, a shame/ honor based culture. We simply don’t know how to reckon with that. We are too frantic. Too ashamed, guilty, and scared. Maybe.

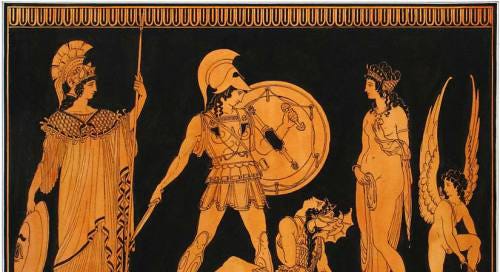

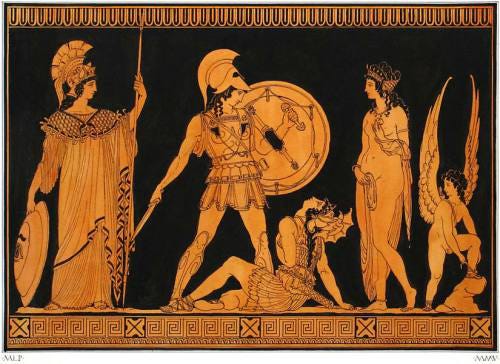

After writing about Greece a few weeks ago, I found myself curious about the Illiad. I missed it, in the same way you miss a person or a place. Curious: I didn’t quite know why I should want to read about eyeballs rolling in the dust, why I should want to read about war, only that I did want to. I didn’t have a copy. G and I planned an afternoon roadtrip to a used bookstore to procure one. Along the way we’d visit a friend and eat in an old favorite restaurant. I tried to remember, out loud, while driving: I hadn’t read the Iliad since that time in my life known as Greece. Or no - I’d read it once after that, specifically studying PTSD. “Rage! Rage be now your song, Goddess…” I bellowed while grasping the steering wheel. He cocked an eyebrow. I massacred a quote by Herodotus, to the effect that war is not celebrated, but is understood. Later I find it: “After all,” he wrote, “No one is so stupid as to choose war instead of peace; in peace children bury their parents, in war parents bury their children.”

Which explained the curiosity: I was trying to grapple with human stupidity.

Epics don’t celebrate war. They are elegies.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Gristle and Bone to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.